Pinyin and pronunciation:

What is Chinese Pinyin? The Chinese Pinyin system is composed of two parts—phonetic alphabets and tone marks. There are four tone marks and five tones in total; one of the tones—light tone, does not need a mark. We’ll come to that later. Let’s see the phonetic alphabets first.

Chinese phonetic alphabets, usually called Chinese Pinyin, are the Latinized version of Chinese characters’ phonetic annotations. It was officially formulated in the 1950s. In the Pinyin system, we have:

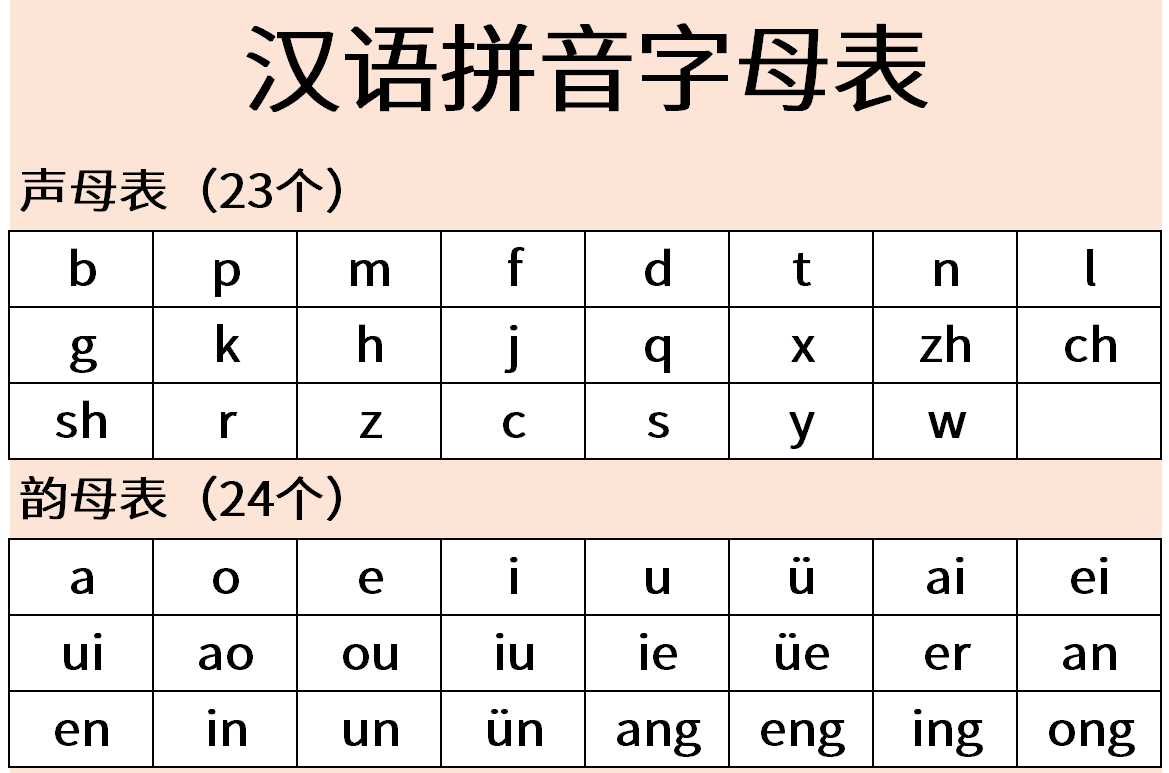

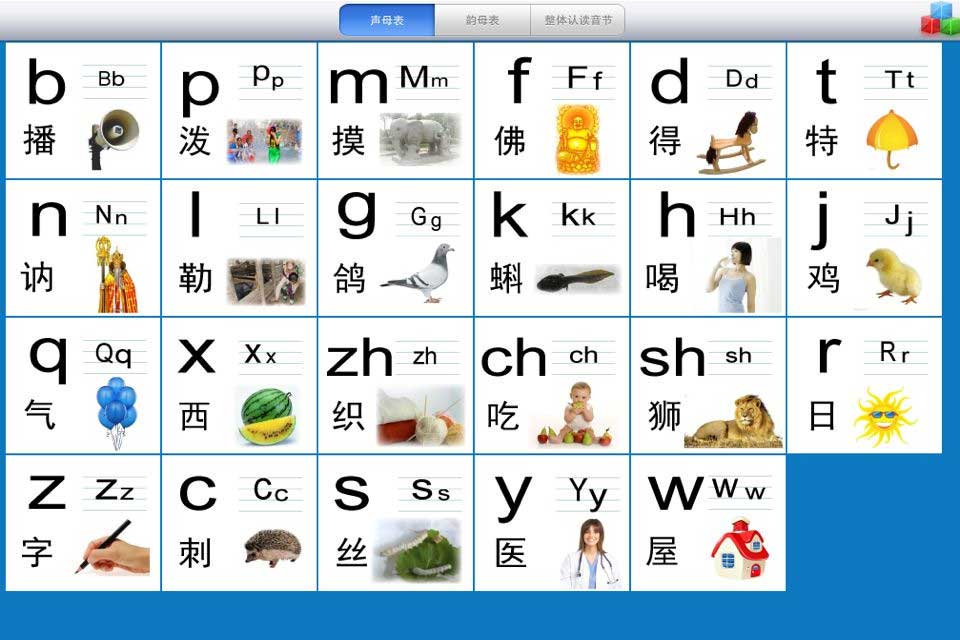

– 23 initial consonants or Shengmu (声母)—they are translated as “initial consonants” because they can only be used to start a word, you will never find those consonants at the end of a Chinese word;

– 24 vowels or Yunmu (韵母)—including 6 simple vowels and 18 compound vowels. The 6 simple vowels are “a” “o” “e” “i” “u” “ü”; and compound vowels include “ai” “ei” “ui” “an” “en” “ang” “ing” etc. You should be noted that except for “ü”, Pinyin alphabets are written exactly the same as they are in English, but you cannot take for granted that they are also pronounced exactly the same way as in English. For example, “ao” is pronounced [au] as in cow.

Pinyin seems complicated, but in fact most of the initial consonants are pronounced in a way similar to consonants in English syllables. For example, we have “k” “g” “d” “t” in Chinese, just like /k/ /g/ /d/ /t/ in English; but these two are probably not easy for foreigners to pronounce: “x” and “q”. People can easily confuse the pronunciation of “x” with “sh” as in shell; actually they are different, and “x” is more like [sh. For example, the word下 (its Pinyin is [xià]) should be pronounced as [shiɑ] meaning “downward”. As for “q”, I don’t think there’s a similar phonetic unit in English. You’ll need quite some practice to pronounce it well.

Another difficult point of learning Chinese is to discriminate between “zh”, “ch”, “sh” and “z”, “c”, “s”. These “zh”, “ch”, “sh” sounds are called cacuminal sounds (翘舌音), that is, consonants articulated with the tip of the tongue turned back towards the hard palate; while the sounds “z”, “c”, “s”, to put it simply, are the non-tongue-turning version of “zh”, “ch”, “sh”.

To be more specific, “z” and “s” are pronounced almost the same as /z/ and /s/ in English, but “c” is different—it is pronounced [ts] as in hats; I don’t think there’s anything sounds like “zh” in English; as for “ch”, it is pronounced [tʃ] as in chair, and “sh” is pronounced [ʃ] as in shell.

On a side note: In Chinese, there is no “v” sound /v/ in Chinese, and that’s why a lot of Chinese students are having trouble pronouncing it correctly while trying to learn English.

How does Chinese Pinyin work?

Basically, the rules are like this:

a). One initial consonant plus one vowel, no matter if it is a simple vowel or a compound one, forms one viable sound for Chinese characters. For example, “t” plus “ing” makes 停[tíng] (pronounced [tiŋ] as in fighting), meaning “to stop”. Of course, you cannot combine initial consonants and vowels randomly; some of the combinations do not make sense at all. For example, “ch” plus “ü” makes nothing.

b). Some of the vowels can be used alone, without an initial consonant. For example, “ai” makes爱[ài] (pronounced [ai] as in light), meaning “love”.

c). There are 16 exceptions to the above rules; they are called “整体认读音节” in Chinese. For example, “chi” cannot be deemed as a combination of “ch” and “i”, and pronounced [tʃi:]. Instead, it is pronounced as something I cannot describe through the roman alphabet. You’ll need a teacher to show you what it is like in person.

In Chinese, there are a very limited number of possible sounds that can be used, no more than 500 actually. The way Chinese differentiate between these sounds is using the tones. As we have mentioned, there are five tones—even tone, rising tone, falling-rising tone, falling tone, and light tone. The first four tones are most important, while the light tone is only used for particles of speech. Each viable sound can be pronounced in four different tones. Mastering the tones is one of the most difficult parts of learning Mandarin and will take some time but is extremely important for a beginner to get right early on. Pronouncing tones in a slightly different way would completely change its meaning as highlighted in the different ways of saying “ma” below:

mā (妈: mother) –even tone

má (麻: hemp, numb) –rising tone

mă (马: horse) –falling-rising tone

mà (骂: scold, swear) –falling tone

ma (吗: interrogative particle) –light tone

It can result in an embarrassing moment if you use the wrong word at the wrong time…

You see the little things over the head of letter “a”? They are tone marks. Light tone does not need a mark, and it is very easy to learn: a weak, natural pronunciation will do.

Now let’s see: 500 possible sounds times 4 tones equals 2,000; but there are over 80,000 characters collected in《中华字海》(a well-reputed Chinese dictionary), which means there are many homophones in Chinese. It will take you a while to master them, but don’t worry; your efforts will be paid off eventually.

How hard are the tones?

Actually many westerners think that Chinese is a difficult language to learn because of its tones, but the English language also has tones. In English, instead of each word having tones, words have different tones depending on the context of the sentence. For example, consider the following sentence:

You look hot

Try and think how many different ways this can be said. It can be said in the way of:

– You look hot ( if you say this with a downward, slightly suggestive tone on the hot it means – you are attractive)

– You look hot (if you say hot in a neutral way, it means – you look like you have a warm temperature)

– You look hot (if you say this with a rising tone at the end, it turns it into a question – are you hot?)

There is also a hidden tone to each sentence in English, that we, as native-speakers don’t realize. If we say a sentence, we are putting tones to some words, and not to others. This is more obvious when we hear a foreign speaker talk in English, although what they are often saying is theoretically correct, it is sometimes hard to gather their exact meaning by the way they speak.

Chinese can seem quite complicated to a non-native speaker. Read how long it takes to learn Chinese! But, you’re never alone. We’ve all struggled to learn a particularly difficult word and fumbled with an unfamiliar pronunciation. Here are a list of tips to self-study Chinese at home!

Of course, the best way to learn is with a native Chinese teacher who can correct your tones and teach you Pinyin. Browse the courses we have, both online and in-person, here!

- China Admissions & ECUST have launched

Fast Track Admissions

- March 24, 2025

- 2025 China Admission Updates - February 27, 2025

- Top 20 Universities to Study Chinese in China for 2025 - February 15, 2025

, based in Beijing. Studied at Peking University & BLCU. Preparing for HSK 6. Hope we can help more talented international students have the same amazing experiences and opportunities that I have had

, based in Beijing. Studied at Peking University & BLCU. Preparing for HSK 6. Hope we can help more talented international students have the same amazing experiences and opportunities that I have had